Identifying the concepts

Well hello there and welcome to update #074!

I believe that identifying the concepts in the content we teach has a number of benefits.

The first is that it makes planning the curriculum more coherent. There are big ideas that run across each domain that provide the unifying story threads which help our pupils make sense of the content. Without them, we are likely to end up in cul de sacs with nothing to stitch the content together.

As Steven Pinker1 argues

Cognitive psychology has shown that the mind best understands facts when they are woven into a conceptual fabric, such as a narrative, mental map, or intuitive theory. Disconnected facts in the mind are like unlinked pages on the Web: They might as well not exist.

When we are able to make the connections, it becomes easier for us to talk to our pupils about how to make sense of new material. This doesn’t need to be heavy duty and it doesn’t need to be done in one go.

It also helps when asked the question ‘Why are you teaching this? Why now?’ While this might be a question often asked on inspection, that’s not the main reason for asking it. The main reason is to help our pupils to make connections between what they are learning now with what has gone before.

The concepts open up the terrain of what we are teaching and help our pupils to make sense of what they are learning. It also helps them make connections for themselves.

The concepts, as ‘holding baskets’ provide the gateways into the subjects and for this reason it’s important to pay attention to them.

There are two main places we can go to in order to identify the big ideas:

The first is the national curriculum importance statements and the second is the high-quality texts we use to teach the subject.

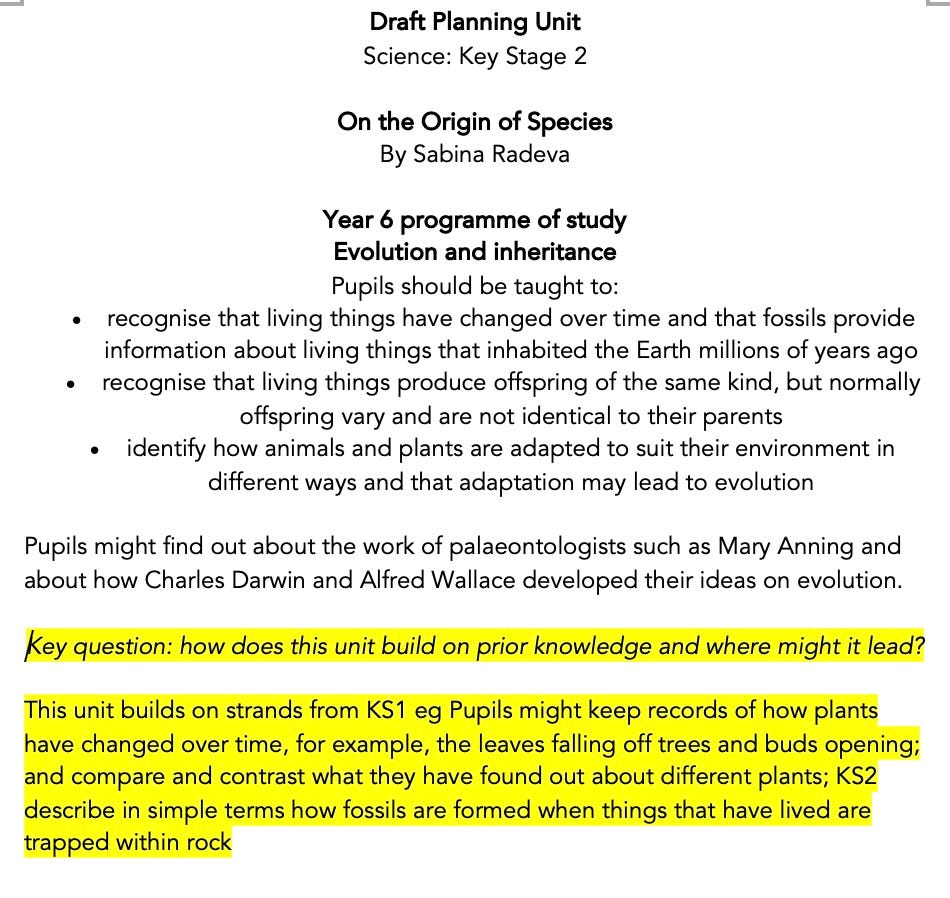

To take an example from the KS2 science programme of study, where pupils need to be taught about the theory of evolution. If we are using a text such as Sabina Radeva’s ‘Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species’, we will find plenty of beautiful vocabulary which will open up the landscape for our pupils. Words such as evolution, extinct, sediment etc. Each of these are domain specific and if we teach them carefully, pupils will be able to gain real insights.

For more on this I’ve developed a draft planning unit, vocab lists and shown how to answer ‘why this, why now?’ which I’ve highlighted below. It’s on The Teachers’ Collection (access via school subscription)

The tier three concept vocabulary is often domain specific. As such they act as gateways into the topic we are teaching. And that is why it is important to pay attention to them. This tier three vocabulary will help our pupils to get to grips with the content. Much of this specialist vocabulary has roots in other languages, very often Latin and Greek. This means we have an opportunity to go into the meaning of the words and to build a story around them.

Let’s take the example of isosceles: if we talk to pupils about what an isosceles triangle is, they can generally tell us. This is because we are very good at teaching definitions.

However, we have an opportunity to take our pupils’ learning deeper if we go into the etymology or the root of the word. Isosceles comes from two Greek words: ‘isos’ is equal and ‘sceles’ is legs.

This means that our pupils have a bigger mental picture of what an isosceles triangle is. It also means that when they bump into isobar or isometric in other parts of the curriculum, they have a clue that it might have something to do with equal. Working in this way is skilling our pupils up for deeper learning across the subjects.

Sometimes the objection to this is that it is too hard! And yet many young children are ‘fluent’ in dinosaurs! And some of them know that the word dinosaur comes from two Greek words: ‘dinos’ is terrible and ‘sauros’ is lizard. If some of them can do this at a young age, they can do it all the way through!

We can do this quite quickly: we just open the browser on an interactive whiteboard, put in the word and the plus + and then etymology and it will show where the root word comes from.

This makes for a good discussion and then when we encounter one of the tier three words, we can ask pupils to find out where it comes from. This could be done for homework and is particularly helpful if we have created vocabulary lists or knowledge organisers.

The schools that are experimenting with exploring the etymology of the concepts are finding that it is the pupils with the lower levels of literacy that are getting the most from this.

When they talk with pupils about why they are getting on so well, they tend to say things like ‘I like finding this stuff out’ and ‘It makes me feel clever!’ I think it is an important element of our work to provide pupils with material that makes them feel clever.

If you want to take these ways of deepening the curriculum across your setting, I have worked with John Tomsett on the Huh Curriculum Leaders online course. John and I explore the ways to make the learning meaningful through films, articles and prompts for discussion.

Until next time

Mary